Radar Intelligence in the Falklands War

By Rodney Barton

The two Super Etendards came in at wavetop height from the north-west, a direction from which the British were not expecting attacks. They popped up to 300ft to sweep the sea with their radars, and detected multiple contacts.

The earlier intelligence provided by the air surveillance operators was spot on – they had found the British carrier task group. Both jets launched their AM.39 Exocet missiles into the formation of ships, and immediately turned for home.

This brief synopsis from Harrier 809 by Rowland White graphically illustrates the importance of radar intelligence during conflict, and it remains a key sensor in modern combat capability today.

With the 40th anniversary of the Falklands War approaching, it is worth remembering this was the world’s first true exposure to modern air and naval combat, and the remoteness of the operating area and distances involved meant that radars played a vital role. Human innovation harnessed the radar technology of the time, using radars in unconventional methods to solve gaps in situational awareness and aid targeting.

Radar intelligence – to put it simply – is the intelligence derived from the collection and analysis of radar track information; range, angle, and velocity (plus elevation if you have a three-dimensional radar). The traditional purpose of a radar sensor is primarily as a battle management tool, but you can also gain significant insight through the analysis of track behaviour and operating patterns. During the Falklands conflict, the intelligence derived from radar often led to follow-on attacks seeking to exploit the insight gained.

The British task force’s primary concern was Argentina’s maritime strike capability. The Armada de la República Argentina had its own carrier task group with the ARA Veinticinco de Mayo operating A-4B Skyhawks armed only with dumb bombs. But this threat was effectively nullified after a British nuclear submarine sank the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano, prompting the carrier to remain in port for the remainder of the conflict.

This left the land-based Dassault Super Etendard strike aircraft wielding newly acquired French AM.39 Exocet anti-ship missiles as the primary Argentine maritime strike option.

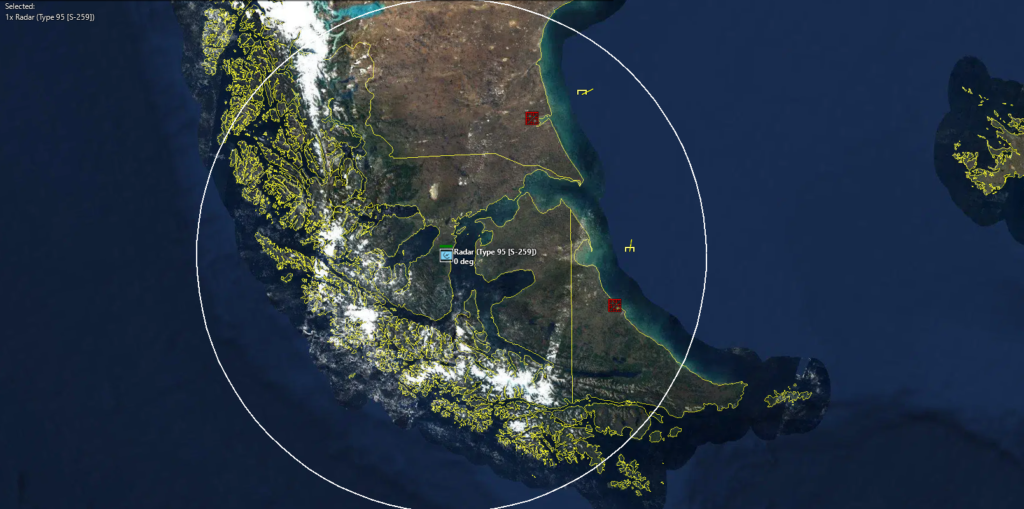

The UK leveraged diplomatic ties with the Chilean government to improve situational awareness of Argentine air operations in the southern Tierra del Fuego region, home to the key Argentine air bases of Rio Grande and Rio Gallegos.

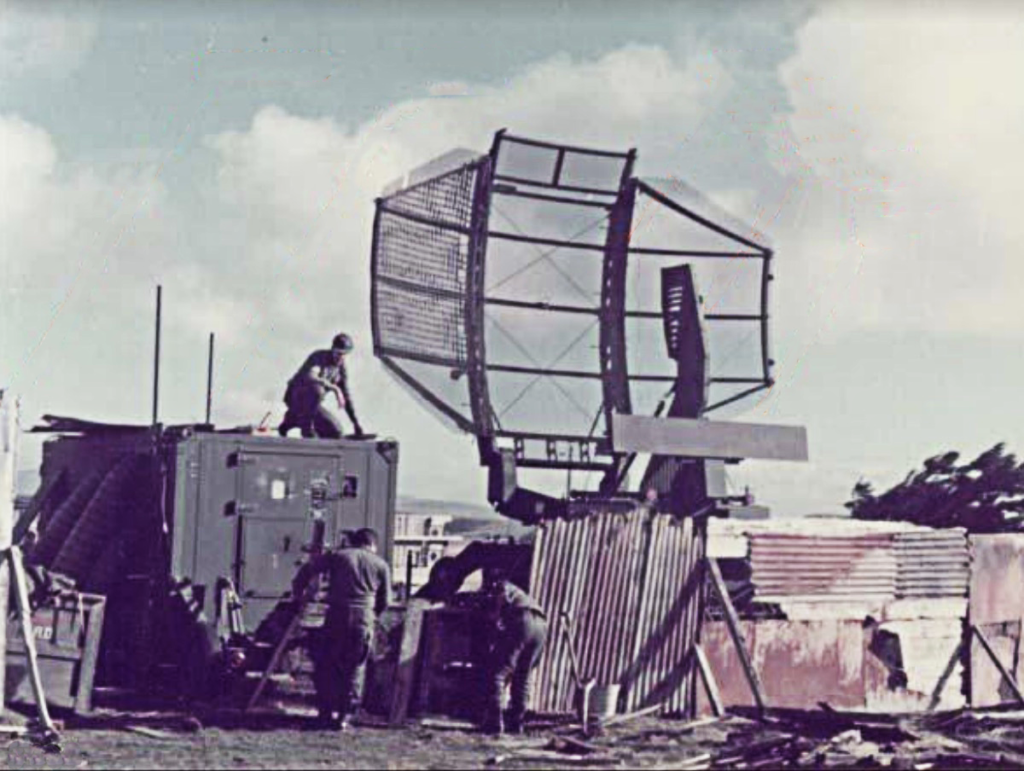

To this end, the British loaned the Chilean Air Force an S259 Marconi air surveillance radar which was deployed in Punta Arenas adjacent the Argentina border, and which provided coverage of the two air bases. As part of Operation FINGENT, this radar integrated with the other Chilean surveillance radars, and provided the British with early warning of aircraft launching from Rio Grande and Rio Gallegos.

To ensure the warning reached the British task force in a timely manner, the British military officer in Chile used a newly developed US satellite communications terminal to pass messages directly to the task force at sea. This ensured the valuable radar intelligence was passed to the right customer at the right time.

But the British task force still suffered from gaps in surveillance gap due to the lack of an airborne early warning (AEW) capability. The British ship-based radars were limited by the radar horizon and could not detect low-flying targets at long range. The new Sea Harrier carrier-borne fighters had the new Blue Fox radar, but this was limited in range and was ineffective as a surveillance system.

This gap had consequences, and during the conflict the low-flying Argentine Super Etendards and Skyhawks sank four Royal Navy destroyers and frigates, and two Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessels.

The gap in airborne radar coverage led to the rapid development of the Sea King Airborne Surveillance and Control (ASaC) platform, but the Sea King system was not ready in time to support the task force. But the Royal Navy has never forgotten the value of airborne surveillance at sea – the Sea King ASaC remained in-service until 2018 and was replaced by the Merlin Crowsnest which made its first deployment aboard the new HMS Queen Elizabeth in 2021.

The Argentineans improvised to extract valuable intelligence on the British task force movements from their limited maritime surveillance assets. This included using a Boeing 707 transport as a maritime surveillance asset. The 707’s long range meant it could shadow the British during the fleet’s transit south from Ascension Island towards the Falklands, while the aircraft’s weather radar allowed it to gradually build a rudimentary but valuable surface picture.

The British countered this surveillance by deploying chaff during these surveillance missions, with the intention being to clutter the radar picture and deceive the Argentineans into thinking the British amphibious ships were also in the formation. The unconventional use of the 707 as a maritime surveillance asset briefly disrupted the British rules of engagement due to civilian air traffic across the South Atlantic – again highlighting the value of airborne AEW to provide extended radar coverage and quicker intercepts.

On the Falkland Islands themselves, the Argentineans deployed a small number of ground-based radars, in particular a modern US-made TPS-43 radar provided significant capability in the hands of competent operators throughout the duration of the conflict. The TPS-43’s crew provided awareness of the air domain, and also tracked British warships in the waters around Port Stanley and beyond.

The TPS-43 was instrumental in two key Argentinean maritime strikes. The first strike exploited clever radar crew analysis of the pattern of Royal Navy Sea Harrier patrol locations, and transits to and from their carriers. This analysis gave Argentine commanders an estimated position of the carrier task group, allowing Argentinean forces to plan and execute the surprise Super Etendard attack described above. This strike sank the container ship MV Atlantic Conveyor, which – while the loss of 12 crew, 10 helicopters it was carrying, and the ship itself was a great loss – probably saved the British aircraft carriers themselves from the incoming Exocets.

The second strike the TPS-43 supported was from the land, using Exocet launch canisters removed from an Argentinean warship and mounted on a trailer. The TPS-43 radar provide surface track information and cueing so the Exocets could engage a British warship south of Port Stanley. This cueing consisted of a pencil marking drawn on the radar scope to indicate optimal weapon employment. This unconventional use of the TPS-43 system demonstrated the versatility of the radar and the creativity of the crew.

The British recognised the threat posed by the TPS-43 and dedicated the Black Buck 5 raid by an Ascension Island-based Vulcan employing Shrike anti-radiation missiles against it. But this raid only damaged the radar with shrapnel, and Argentine repair crews flown in the from the mainland had restored its operations the next day.

The Falklands War directly informed Australian capability developments, particularly in the air and maritime domains. Key examples include the Jindalee Over the Horizon Radar Network (JORN) for wide area surveillance, and the development of the Boeing E-7A Wedgetail AEW&C aircraft. Additionally, Australia’s CEA Technologies has developed world-class active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars and delivered them on the ANZAC class and future frigates, as well as the Enhanced-NASAMS system for the Australian Army’s new Project LAND 19 Phase 7B short-range air defence system.

The continuing evolution of radar technology provides further opportunity to derive actionable intelligence from these sensors. Increased sensor performance provides timely warning, with better resolution to positively identify tracks and understand track behaviour. Radar will maintain a key role in ‘kill chains’ providing the fidelity of information required to ensure effective platform and weapon employment. The 40th anniversary of the Falklands War reminds us of the value of technical radar systems, coupled with creative humans, in conflict.